Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

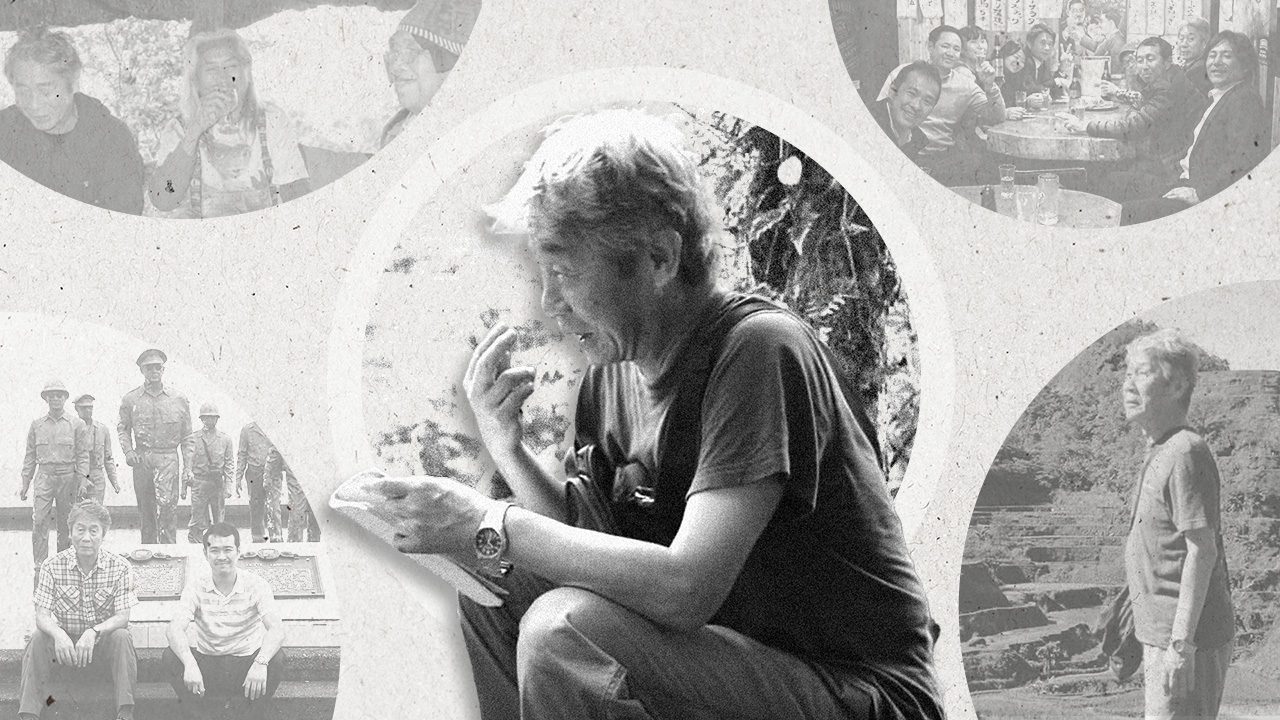

For almost half a century, Hiromu Shimizu led Philippine studies in Japan. A cultural anthropologist and professor emeritus at Kyoto University, he contributed to academic and cultural exchange between our two countries.

Prof. Shimizu, popularly known in the Philippines as Hiro, trained many researchers — I am one of them. As an undergraduate student, I became interested in Philippine studies after being absorbed in work camp activities to build simple infrastructure, such as water systems in the rural barangays of Leyte, and being deeply touched by the kindness of the people there.

For my graduation thesis, I read many books and papers about the Philippines and found Prof. Shimizu’s works to be the most inspiring and exciting among studies written by Japanese scholars. While reading his works, I could not help but roam around the library with great excitement. He vividly described the lived experiences and world views of Filipinos, and he himself was deeply involved in their activities for their lives and rights.

I went to a graduate school where he taught. I wanted to change my major from political science to cultural anthropology, but he did not allow it. He explained that his influence would trap me if I majored in the same discipline and area as his. Instead, he insisted that I should retain my freedom to forge my own path. This is why I became an interpretive political scientist who loves field research and writes ethnographies like a cultural anthropologist.

Hiro was born and raised in post-war Yokosuka, where a United States naval base for the Seventh Fleet exists. Yokosuka became the logistic and a “rest and recuperation” base for the US Army during the Korean War in the early 1950s and the Vietnamese War in the late 1960s. American soldiers roamed the city with a swagger, made trouble, and sought sex with Japanese women. Their US dollars invigorated the local economy.

The American power’s massive and close presence significantly influenced young Hiro’s personality development. While he hated American soldiers who expressed the desire for alcohol, sex, and violence, he yearned for American popular culture, such as movies and music. In 1970, as the atmosphere of the anti-American student movement lingered, Hiro entered the University of Tokyo. To emancipate himself from the American hegemony, he majored in cultural anthropology and tried to conduct research in China.

However, China was amidst the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, so he decided to study the indigenous people of Taiwan. In 1972, though, with the restoration of diplomatic relations between Japan and China, it became impossible to conduct research in Taiwan. The situation forced him to change his research field to the Philippines temporarily. He was impressed by how the Philippines resembled Yokosuka in its love-hate relationship with America. He had set his sights on China to distance himself from American influence, but was back to square one. Moreover, the Philippines was considered to be an undesirable place for cultural anthropology because Western researchers regarded Filipino lowlanders as “people without culture” and indigenous people’s culture as too simple.

Rather than deny these unexpected contingencies of life, Hiro actively embraced them, enjoying the encounters and friendships with Filipinos and accompanying their activities with respect. He was not someone who proactively tried to manage himself, others, and the environment in order to carry out his research plans. He was actively involved in the contingencies, honestly interacting with the people he met, accompanying them in their activities, and trying to “respond” in his own way. He was actively reactive, valuing what he called “response-ability.”

In the Philippines, Hiro first studied in a graduate course of Professor Mary Racelis at the Ateneo de Manila University. He learned from her the importance of reciprocity in Philippine society and began thinking vaguely that he needed to give back to the people he studied. Hiro also admired Professor Racelis’s commitment to the urban poor people’s movement in Tondo with the “People Power” slogan. He regarded her as a role model of an engaged cultural anthropologist.

In 1977, Hiro started fieldwork on the Aytas in the foothills of Mount Pinatubo for 20 months. Hosted by Ayta friends, he enjoyed learning about their lives and culture. The experience became Pinatubo Aytas (1989), in which he discussed how Aytas had tamed the shock of shocking events and prevented a breakdown of social order.

Inspired by the dramatic People Power Revolution in 1986, he expanded his research into popular culture and politics, trying to offer a different account of the event than that of political scientists. His Politics in Culture (1991) explained how Filipinos interpreted the political event within the martyrdom narrative in Catholicism and how it encouraged them to risk themselves in the struggle against the dictatorship. Following the research, he studied Filipino nationalism in popular culture and discussed how Filipinos, embracing the agony of colonial rule, projected a desirable self into the future to return to it. This study was also a message to the Japanese to relativize their exclusivist nationalism based on the fantasy of an essential culture that continued from the eternal past.

In 1991, on his birthday coincidentally, Mount Pinatubo erupted. He then went on a relief mission to repay his Ayta friends who were suffering from the disaster. He gave up his research because he thought exploiting their predicament for academic achievements was unethical. However, impressed by the Ayta’s dramatic recovery process as a dignified indigenous people, he eventually resumed research. Orphans of Pinatubo (2001) presents many narratives of Ayta, which Hiro dared not to edit or analyze to avoid depriving their own voices by speaking for them as a researcher. He emphasized that the Ayta survivors had the voices and stories to tell, and we must listen to them first.

In the 2000s, attracted to the forest and cultural restoration activities of artist Kidlat Tahimik and Ifugao leader Lopez Nauyac whom Kidlat admired as his mentor, Hiro became actively involved in their activities. At Nauyac’s request, Hiro introduced a Japanese NGO to him and obtained a large grant from JICA and others to support Ifugao’s afforestation campaign to protect their heritage of rice terraces. Grassroots Globalization (2019) analyzes the process and consequences of the movement to which he himself was committed. It also discusses how local cultural practices by the Ifugao, who have come to work around the world, have tamed the powerful forces of globalization.

His latest and last book, Aeta: Future in the Ashes (2024), chronicles the events of the past 40 years he accompanied them, documenting with many colored photos the Ayta’s dramatic rebirth as new human beings after the Pinatubo eruption and great suffering. He came up with the book project to share his historical and intimate photographic records with Ayta friends. When he presented to friends the old photos he had discovered from his archives, they were moved to tears because they could see their deceased families after many years. Hiro also had the idea to translate the book into English, and Professor Racelis talked to the Ateneo de Manila University Press about it, but the plan did not materialize.

Regrettably, the last monograph he was working on, tentatively titled “Our Father MacArthur,” was not completed either. It was an auto-ethnographic study of the entangled relationship between Japan, the Philippines, and the US through the lens of his own life experiences.

According to him, postwar Japan and the Philippines are not only perpetrators and victims of war, or advanced and emerging countries, but also America’s half-siblings in Asia. Both countries were “emancipated” by American violence and tamed to embrace pro-American sentiments under its shadow. Yet, while Filipinos cannot forget the colonial past that they want to forget, the Japanese have forgotten the past that they must not forget. Hiro used to say that we Japanese should learn much from the Philippines’ suffering and pursuit of creating a new self with dignity and freedom.

Hiro did not like the Japanese to speak ill of the Philippines, and Japanese researchers to make achievements by pointing out the country’s shortcomings. He said that it was arrogant of the Japanese to criticize the Philippines from above, even though they were indebted to the kindness of the Filipino people and could not do any work without their cooperation.

Hiro valued learning from Filipinos and responding to their calls. In this process, he believed he could re-constitute himself to be reborn as a new and freer person. In downtown Manila, I remember him dancing to a band playing Bob Marley’s “Get Up and Stand Up” and smiling with a beer in his hand, saying, “Because life is more fun in this way.” Throughout his half-century of Philippine studies, he developed an optimistic belief that human beings are capable of achieving creative recovery, even across generations, in the face of any unexpected events, adversities, or catastrophic circumstances.

Earlier this year, he suffered from interstitial pneumonia and walked with an oxygen tank, but he was still planning trips to the Philippines, translating his book into English, and writing his next book. His body was built for summer, for the Philippines, and he and we believed that he would regain his strength with the coming of the new spring. Sadly, that was not to be.

Hiro passed away on February 22, 2025. Today, Sunday, June 15, he would have turned 74. – Rappler.com

Wataru Kusaka is a professor at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. He is the author of Moral Politics in the Philippines: Inequality, Democracy and the Urban Poor (National University of Singapore Press and Kyoto University Press, 2017) and Anti-Civic Politics: Democracy and Morality in the Philippines (Hosei University Press, 2013), among several publications.