Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC News World

BBC

BBCEvery morning, Rosa Chamami woke up on cardboard scraps in a garden kitchen.

Housing Housing made 800,000 high-tech solar panels. Now they turn on the fire.

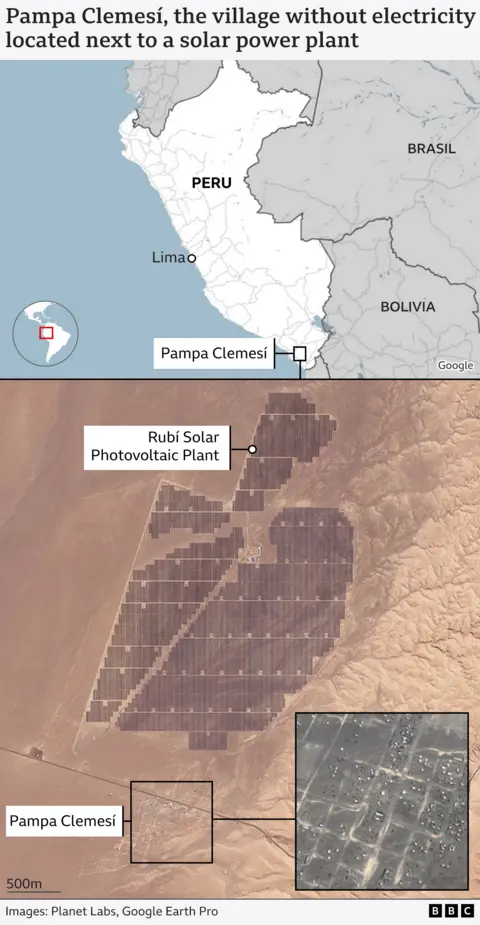

Between 2018 and 2024, these panels were installed on Rubí and Clemesí, in two massive sun plants in the region of Peru, 1,000 kilometers south of the capital, Lima. Together, they form the largest complex solar in the country, and is the largest of Latin America.

From his house to the small location of Pampa Clemesí, the rows of panels that glow under the white floods of Rosa. Rubí plant is 600 meters away.

However, his house – and the rest of the town – it remains full of darkness without connecting the plant to the grids.

Pampa Clemesí’s 150 residents do not have access to the national network of power.

A few troops of Rubí’s operators, they have given origins, but most cannot pay the batteries and converters required to work. At night, they use the flashlight, or just live in the dark.

The paradox is striking: Rubí Solar Centers produces about 440 GWh a year to supply electricity to 351,000 homes. Moqueuu, where there is a plant, is an ideal solar energy center, more than 3,200 hours per year, more than most countries.

And this contradiction is even stronger in a country that lives a renewable energy boom.

Only in 2024, the generation of renewable energy generation increased by 96%. The power of the sun and wind depends on copper due to high conductivity, and Peru is the second largest producer in the world.

“In Peru, the system was designed around profitability. It has not been effort to link the sites in charge,” explained the energy expert in Santa María University of Carlos Gordillo Arequipa.

Origen says he has fulfilled his responsibilities.

“We have also included in the Governing Project to carry electricity electricity and also form the first phase of the electrification project.” Marco Fragale, Orygen’s executive director of Peru I have told the Executive Director of Peru, BBC News Mundo, Spanish BBC service.

Fragale adds that nearly 4,000-meter underground cords of underground to provide an online line for the town. The investment of $ 800,000 has ended, he says.

But the lights are not yet moved.

Last step – Connecting the new line to individual homes – it is the responsibility of the government. Depending on the plan, the Mines and Energy Ministry must put about two kilometers of cord. The work began in March 2025, but has not started.

BBC News tried to contact the Ministry of Ministry and Energy, but has not received an answer.

The small house of Rosa does not have a plug.

Every day, he walks through the village, hope someone can save some electricity to load your phone.

“It is essential,” he explained that he has to have a relationship with his family in Bolivia.

One of the few people who can help is the Rubén Pongo. Wider house – with courtyards and various rooms – a chicken group fights the space of the roof between the solar plate.

“The company gave most citizens to the solar panels,” he noted. “But I had to buy battery, converter and cables and pay for the installation.”

Rubén dreams something else: refrigerator. But it is only 10 hours a day, and the daylight, not a cloudy day.

He helped build Rubí plant and then worked in maintenance, cleaning the panels. Today, he manages the warehouse and encourages the company to work, even if the plant has been on the road.

The Peruvian law is prohibited by crossing the Panameneric Highway.

From his roof, Rubén is a cluster with bright buildings in the distance.

“That’s the plant substation,” he noted. “It looks like a small town.”

Residents began to settle in Pampa Clemesía in the early 2000s. These include Pedro Chará, 70. 500,000 panel Rubí Plant has seen almost door.

A large part of the town is built of the exclusion materials of the plant. Peter said the beds are coming from the woods.

There is no water system, not sewage, littered collection. The town had a population of 500, but due to scarce infrastructure, most left – especially in Covid-19 pandemic.

“Sometimes, after waiting for so long, you feel like killing water and electricity, killing. That’s it.” Kill, “he said.

Rosa in his aunt’s house in a hurry, hoping to catch the last of the daylight. Tonight, dinner is looking for a small neighbor group that shares meals.

In the kitchen, a gas kitchen heats a hole. Their only light is a flashlight with solar power. Dinner is a sweet tea and a fried dough.

“We only eat what we can keep at room temperature,” Rosa says.

Without the refrigerator, foods that are rich proteins are hard.

Fresh produce requires a 40-minute bus ride to Moquoa – if they can afford.

“But we don’t have money to take the bus every day.”

Without electricity, many Latin Americans cook with wood or kerosene, to jeopardize respiratory diseases.

In Pampa Clemesí, residents use gas when they can’t afford to pay – when they can’t be wood.

Torchlight pray for food, shelters and water, and then eat silently. They are 19:00, their last activity. No phones. No TV.

“Our only light is these little flashlights,” Rosa says. “They don’t show a lot, but at least we can see the bed.”

“If we had electricity, people would return,” says Pedrok. “Because we had no choice but to stay. But with light, we could build the future.”

The smooth breeze includes the streets of the desert, lifting the sand. A layer of dust is located on the main square lamp, waiting to be installed. Signs of the winds coming – and there will be no light soon.

For sunbathes, like Rosa and Peter, darkness extends until the sun. So the government has a hope that will play one day.

As many nights before, they prepare another evening without light.

But why are they still living here?

“Because of the sun,” Rosak has certainly replied.

“Here, we always have the sun.”