Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

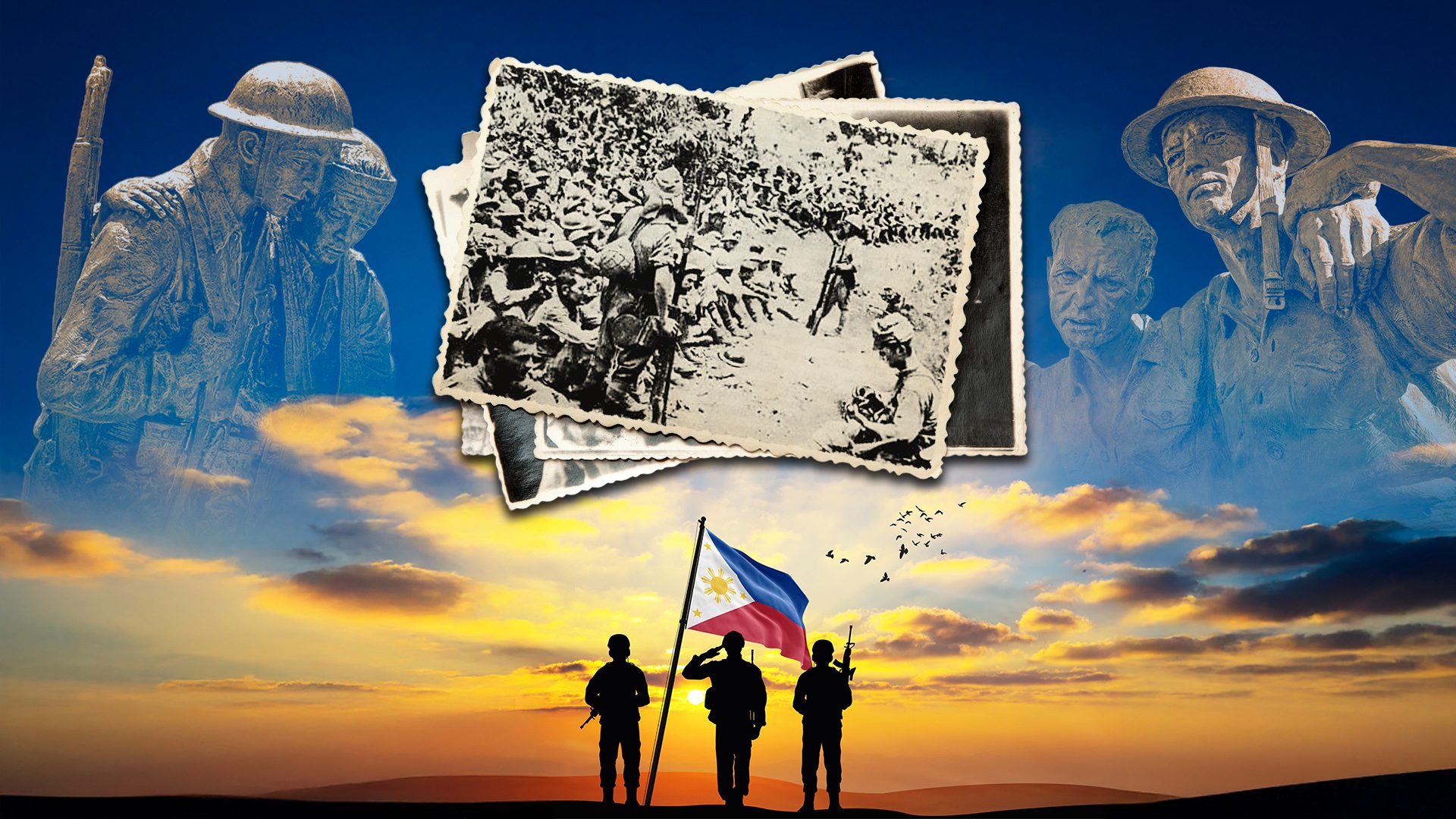

This Independence Day, I pay my respects to the World War II veterans, defenders of Corregidor and Bataan, and to our beloved PMA Class ’40 heroes

To the uninitiated, an army brat is a child of a military officer and not BRAT as millennials use the word nowadays.

There exists a Viber chat group called AFP (Armed Forces of the Philippines) Brats established by Arturo “Toto” Acosta, son of the late General Manuel Acosta (Philippine Military Academy, or PMA, Class 1940). The chat group was a welcome initiative and considered quite natural since we all shared a common history — our fathers having graduated from the PMA Class ’40 and many among us growing up together either within or outside the military camps.

As army brats, we shared the same slang as our father’s had in the academy:“Unbecoming!”, “Sonamagun!”

In 2000, the book Closer Than Brothers: Manhood at the Philippine Military Academy by Alfred W. McCoy was launched in National Bookstore with my father, the late Colonel Deogracias F. Caballero, delivering the opening remarks. McCoy is an American historian and educator specializing in the history of the Philippines and US foreign policy.

Caballero was one of the resource persons of McCoy in the telling of the story of the PMA beginning with Class ’40 to the class of ’71 under the late president Ferdinand E. Marcos. In broad terms then-president Manuel Quezon, feeling the threat of a Japanese invasion, enacted the National Defense Act in 1935, giving way to the creation of a corps of officers who would recognize the authority of the civil government and be loyal to its Commander in Chief.

Quezon engaged the help of US General Douglas MacArthur to establish the PMA, one might say a local version of West Point; well, it was really a replica of West Point.

“Courage, Loyalty, Integrity” was the academy’s motto and were the principles that were ingrained in the psyche of the young cadets, many of them ages 17 to 18. Little did they know of the dangers and horrors they would have to face in the coming World War II.

I sometimes think of my millennial son who, one evening, said to me, “Mom, can the driver take us to the rally in Batasan?” And I said, “There’s something seriously wrong with that statement.” Like going to war without a gun? Or as my mother would say when were slacking, “If this was a war, you would have been shot by now.”

To be fair, my sons did their military service in Finland: six months for the army, and my youngest did nine months in the navy. And I do think of them living right on the border of Russia, and may be called up anytime, but as the Finnish President Stubb said, “We’ve got this.” But I digress.

McCoy relates that Deogracias Caballero and Cesar Montemayor, as cadets in their 3rd year, were chosen to serve on the honor committee, a committee aimed at steering intense rivalry and competition to a more positive direction to preserve unity.

Even after graduation, Caballero and Montemayor continued to exercise some moral leadership among the Class’40s. The cadets were held to a very high standard of honor that any infractions on the honor code were brought in front of the honor committee and, if found guilty, were summarily dismissed. No appeals.

Four years in the PMA resulted in a strong bond among the classmates that would carry them through the trials of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

McCoy features the memoirs of Col. Joe Mendoza (also Class ’40) detailing his experience in the Death March together with Caballero, (classmate) Francis Lumen and fellow officer Ben “Toots” Tolentino. The unbreakable bond between the four classmates proved to save Mendoza’s life when they refused to give up on Mendoza who was suffering along with malaria and chills, even though they themselves were suffering from hunger, thirst and exhaustion.

The Death March lasted from April 9 to 17 in 1942, with approximately 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers who were forced to march from Mariveles, Bataan to San Fernando, Pampanga, a distance of approximately 105 kms and another 13 kms from Camp O’Donnel, an internment camp in Capas, Tarlac, where conditions were said to be worse than in the Death March.

In Mendoza’s memoir he describes the scene in the NARIC warehouse in Lubao teeming crowds of prisoners “lying down, squatting, or seated on their haunches, surrounded by fecal matter with maggots and flies the size of bees.”

It’s of little wonder that our fathers never wanted to talk about the war.

At different times from April to September 1945, prisoners of war were released.

Mendoza himself was met by his mother at the Tutuban train station. He then sought out Caballero and invited him and his wife and daughter to dinner at which point, Mendoza’s mother offered a place for the young Caballero family to stay with them on their farm. A show of gratitude for saving Mendoza’s life.

The shared experience and suffering strengthened the ties between the classmates keeping them “Closer Than Brothers” for 50 years.

Many decades later, many wondered how did we go from Courage,Loyalty, Integrity to “no corruption, no patronage, no coups.

In his welcoming remarks, at the launch of Closer Than Brothers, Caballero said, “Is it honorable to use your firearm against the very government that gave you that firearm?” Clearly loyalty to the commander-in-chief remained strong in Caballero even in the year 2000. “I understand that female cadets are now being admitted to the PMA. Perhaps we will have less corruption with women serving in the military (Women’s lib thanks you Daddy).”

The army brats remain hopeful. We salute our fathers for fighting for a free, independent, and democratic Philippines.

This Independence Day, I pay my respects to the World War II veterans, defenders of Corregidor and Bataan, and to our beloved PMA Class 40 heroes. May you all rest in peace in courage, loyalty, integrity. – Rappler.com