Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

AFP

AFPLevels of the most significant planet-warming gas in our atmosphere rose faster than on record last year, scientists say, leaving a key global climate target hanging by a thread.

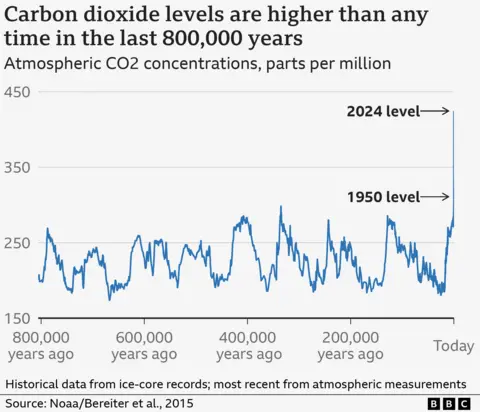

Carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations are now 50% higher than before humans began burning large amounts of fossil fuels.

Last year, fossil fuel emissions hit record highs, and the natural world struggled to absorb as much CO2 as wildfires and droughts piled up more in the atmosphere.

The rapid rise in CO2 is “incompatible” with international commitments to try to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, the Met Office says.

This was the ambitious goal that almost 200 countries agreed to at a major UN meeting in Paris in 2015 in order to avoid some of the worst effects of climate change.

This was confirmed last week 2024 was the hottest year on recordand the first calendar year in which the average annual temperature was more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

That didn’t break the Paris target, which refers to a longer-term average over decades, but rising atmospheric CO2 effectively puts the world on track.

“Limiting global warming to 1.5C would require slowing the rise in CO2, but in reality the opposite is happening,” says Richard Betts of the Met Office.

The long-term increase in CO2 is undoubtedly due to human activities, mainly from the burning of coal, oil and gas, and deforestation.

Records of Earth’s climate in the distant past from ice cores and marine sediments show that CO2 levels are at least as high as the last two million years, according to the UN.

But the increase varies from year to year, thanks to differences in the way the natural world absorbs carbon, as well as fluctuations in human emissions.

Last year, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels reached new highs, according to preliminary data from the Global Carbon Project.

There were also consequences El Niño natural phenomenon – Where surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean become unusually warm, influencing weather patterns.

The natural world has absorbed roughly half of humanity’s CO2 emissions, for example through additional plant growth and more of the gas dissolving in the ocean.

But that extra warmth from El Niño against the backdrop of climate change meant that the earth’s natural carbon sinks weren’t absorbing as much CO2 as usual last year.

Forest fires, including those in regions typically unaffected by El Niño, also released additional CO2.

“Even without the boost from El Niño last year, CO2 increases driven by fossil fuel burning and deforestation would now exceed (the UN’s climate agency) IPCC’s 1.5C scenarios,” Professor Betts says.

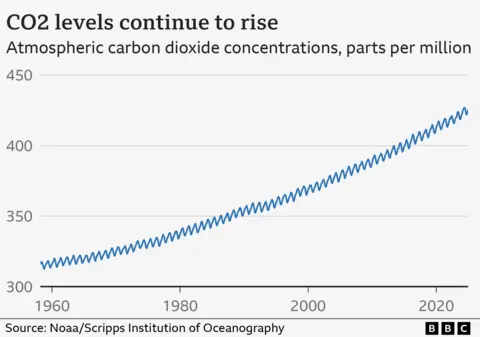

These factors caused CO2 levels to rise by nearly 3.6 parts per million (ppm) molecules in the air between 2023 and 2024 to a high of more than 424 ppm.

This is the highest annual increase since the Mauna Loa atmospheric research station in Hawaii was first built in 1958. Located on the side of a volcano in the Pacific Ocean, the resort is ideally located away from major sources of pollution. To monitor global CO2 levels.

“These latest results further confirm that we are moving faster than ever into uncharted territory as the upwelling continues to accelerate,” says Professor Ralph Keeling, who leads the measurement program at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the US.

AFP

AFPThe record increase adds to concerns that the natural world is becoming less capable of absorbing planet-warming gases in the long term.

Arctic tundra is becoming a major source of CO2, thanks to warming and frequent fires, according to the US science group NOAA.

The The ability of the Amazon rainforest to absorb CO2 it is also suffering from droughts, forest fires and deliberate deforestation.

“It’s an open question, but it’s something we need to look at very carefully and look at carefully,” Professor Betts told the BBC.

The Met Office predicts that the increase in CO2 concentrations in 2025 will be less extreme than in 2024, but will still be significantly short of meeting the 1.5C target.

La Niña conditions – where surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean are cooler than normal – have replaced El Niño, allowing the natural world to absorb more CO2.

“While there may be a temporary respite with slightly cooler temperatures, warming will resume because CO2 is still building up in the atmosphere,” says Professor Betts.