Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Our father’s body was lying on a leaden metal base. He was covered up to his collarbone with a simple white sheet, over which his shaved head was supported by a stone headrest. Looking at him, it was as if his body had shrunk along with his deceitful life.

I shuddered. The visiting room at Omega Funeral Home was as cold as a meat locker, while in the off-season Lagos was turned into a sauna. As I held my brother Femi’s hand, I remembered the pain that washed over me when he called to tell me the news of our father’s death.

“Aniki,” Femi began.

“I was about to call you,” she began. “Aniki,” Femi interrupted, his voice more firm this time.

“Yes?” I answered.

“My father died last night, at three o’clock in the morning,” he said.

I didn’t ask for anything. I said nothing. I dropped my phone and slid forward, burying my face in my hands. I felt so much pain that I couldn’t cry.

Our father, Joshua Kayode Adepitan, was hospitalized with a fever for one day and died the next day due to a colon obstruction, a condition we later discovered was treatable. It’s only been three months since I last saw my father, during my annual visit after New Year’s.

For years, I arranged for my father to travel to visit me in the UK to attend celebrations and spend time with me. However, the day before his arrival, he always called for a cancellation with the excuse of some ongoing business deal or warnings from his religious prophets, who warned him about his safety and urged him to stay home and fast. So instead I traveled to him.

After his death, Femi and I traveled from my home in London to Lagos to oversee the arduous task of burying an accomplished and respected man who had lost everything he loved and lived the last two decades of his life isolated in the dark shadows of failure and disrepute.

“We will honor him with a traditional Yoruba funeral,” Femi said, trying to console me. “We will celebrate the man he once was.”

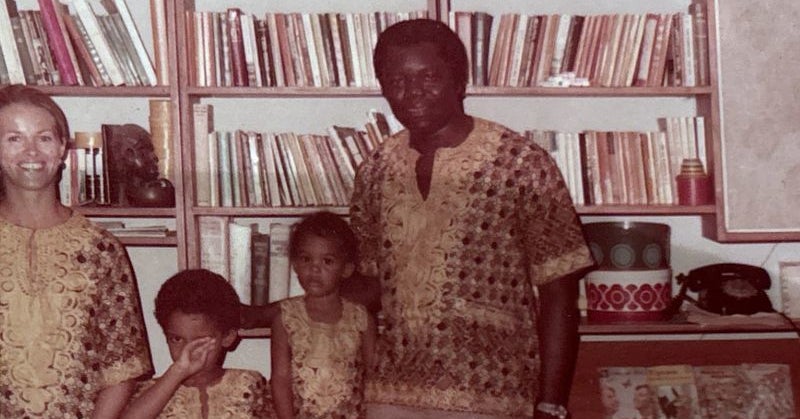

My father was my hero growing up. He was a proud Yoruba man who worked his way from obscurity and poverty in rural Nigeria to a life of success and respect. A natural storyteller, he commanded every room he entered with his presence and delighted audiences with his wit. I loved listening to his stories about growing up in the colonial era, about winning scholarships to universities abroad, about meeting my British mother in Sweden, and about his triumphant return home to found two successful companies and build a beautiful house in the affluent suburbs of New York City. Lagos.

I loved the times he would let me accompany him to his furniture factory to inspect newly completed orders waiting to be delivered to offices and hotels. I loved the way he took the time to explain how to identify different types of wood by smell and patterns etched into the grain or when he let me ride shotgun on his speedboat while he ran the engines along the Atlantic coast, and of all times he told my favorite story about his grandmother who encouraged his ambition by saying Him: “You can do anything you set your mind to.” Our little family unit revolved around my parents. It was the source of our stability, security and enjoyment. All I wanted was to be like my father.

After the Nigerian economy collapsed under decades of military dictatorship, the government closed my father’s charter airline, and his furniture company began to go bankrupt due to a sharp decline in demand. He stopped going to his office, playing squash at the Metropolitan Club, and traveling the world with our mother and their friends.

My father withdrew from the world, spending hours on the phone with faceless “business associates” over long, disconnected phone lines. Threatening strangers showed up at our gate at all hours of the day and night demanding money. Fearing his shady new business dealings, our mother divorced him and fled the country, quickly changing her name and severing all ties with him. Our father became a recluse, cutting off all contact with his extended family and all his friends. By then, Femi and I were in our early twenties and studying abroad.