Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Climate and science journalist

Data reporter

Getty Images

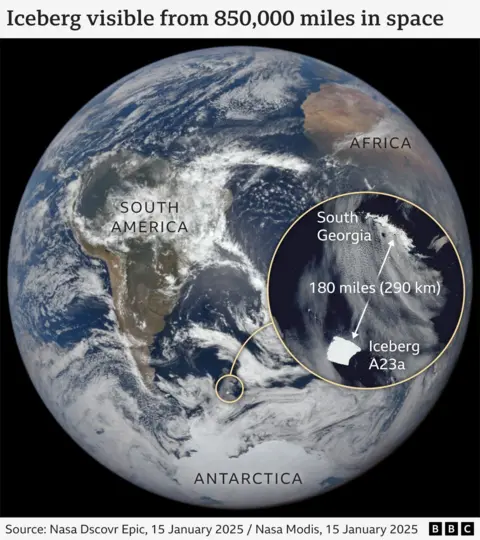

Getty ImagesThe world’s largest iceberg is crashing into a British island, putting penguins and seals at risk.

The iceberg is rolling north from Antarctica towards South Georgia, a rugged British wildlife refuge, where it could smash ashore and break into pieces. Today it is 173 miles (280 km).

Many birds and seals died in the frozen coves and beaches of South Georgia when the giant icebergs of the past stopped feeding them.

“Icebergs are inherently dangerous. I would be very happy if we lost them completely,” sea captain Simon Wallace told BBC News, speaking from the South Georgia government ship Pharos.

BFSAI

BFSAIA group of scientists, sailors and fishermen around the world are analyzing satellite images to monitor the daily movements of this queen of icebergs.

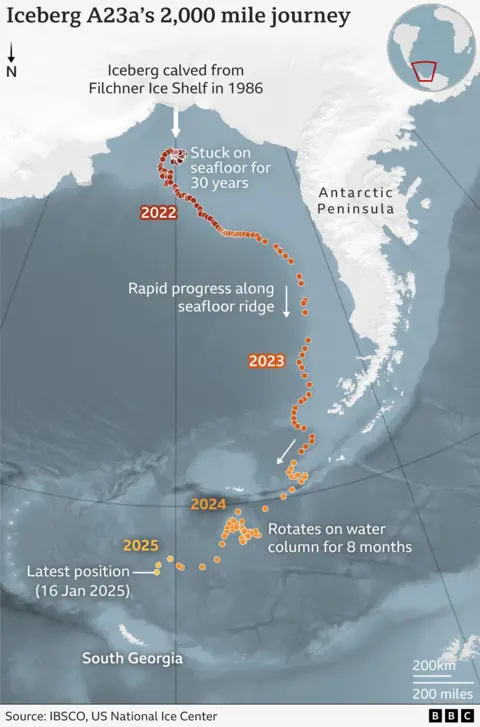

It is so Known as A23a and is one of the oldest in the world.

It broke away from the Filchner Ice Shelf in Antarctica in 1986, but remained on the seabed and was caught in an ocean eddy.

Finally, in December, it was released and is now on its final journey, speeding towards oblivion.

Warmer waters in northern Antarctica are melting and undermining its vast cliffs, 1,312 feet (400 m), taller than the Shard of London.

It once measured 3,900 square km, but the latest satellite images show that it is slowly disintegrating. Today it covers about 3,500 square km, roughly the size of the English county of Cornwall.

And great sheets of ice are breaking up, plunging into the waters around its edges.

The A23 could break into large pieces any day, and then hang around for years, like floating cities of ice drifting unchecked across South Georgia.

This is not the first giant iceberg to threaten South Georgia and the Sandwich Islands.

In 2004, one called A38 ran aground on its continental shelf, leaving dead penguin chicks and seal pups on the beaches as large chunks of ice blocked their access to food.

The territory is home to prized colonies of king emperor penguins and millions of elephant and fur seals.

“South Georgia is in the iceberg lane, so impacts are expected for both fisheries and wildlife, both of which have a strong capacity to adapt,” says Mark Belchier, a marine ecologist who advises the South Georgia government.

Sailors and fishermen say icebergs are a growing problem. In 2023, an A76 gave them a scare as it approached the ground.

“There were chunks going up there, they looked like great towers of ice, a city of ice on the horizon,” says Mr Belchier, who spotted the iceberg while at sea.

Those slabs still protrude around the islands.

“It ranges from the size of several Wembley stadiums to parts the size of your table,” says Andrew Newman of Argos Froyanes, which operates in South Georgia.

“Those pieces basically cover the island – we have to make our way,” says Captain Wallace.

The sailors on his ship must be constantly alert. “We have the lights on to try to see the ice; it can come out of nowhere,” he explained.

The A76 was a “game changer” according to Mr Newman, “having a huge impact on our operations and keeping our ship and crew safe”.

Simon Wallace

Simon WallaceThe three men describe a rapidly changing environment with year-on-year glacier retreat and volatile sea ice levels.

Climate change is unlikely to have been behind the birth of A23 because it was born so long ago, before the major effects of the temperature rise we are seeing now.

But giant icebergs are part of our future. As Antarctica becomes more unstable, with warmer ocean and air temperatures, larger portions of the ice sheet will break up.

Before its time is over, however, A23a has left a gift for scientists to share.

A team from the British Antarctic Survey on the research vessel Sir David Attenborough found it near the A23 in 2023.

Scientists seized a rare opportunity to investigate what mega icebergs do to the environment.

Tony Jolliffe/BBC

Tony Jolliffe/BBCThe ship entered a crack in the iceberg’s giant walls, and PhD student Laura Taylor collected precious water samples 400 meters from its cliffs.

“I saw a huge wall of ice way above me as far as I could see. It’s different colors in different places. Pieces were falling off – it was pretty cool,” he explains from his laboratory in Cambridge, where he is based. analyzing the samples.

His work examines how meltwater affects the carbon cycle in the Southern Ocean.

Getty Images

Getty Images“This isn’t just the water we drink. It’s full of nutrients and chemicals, as well as tiny animals like phytoplankton frozen inside,” says Ms Taylor.

As the iceberg melts, it releases these elements into the water, changing the physics and chemistry of the ocean.

This could store more carbon in the deep ocean as particles sink from the surface. This would naturally block some of the planet’s carbon dioxide emissions that contribute to climate change.

Icebergs are unpredictable and no one knows exactly what they will do.

But soon the behemoth should appear, on the horizon of the islands, as big as the land itself.