Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC Eye Investigations

BBC

BBCWhen Zhang Junjie was 17 years old, he decided to protest the rules made by the Chinese government outside his university. A few days later he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital and treated for schizophrenia.

Junjie is one of dozens of people identified by the BBC who were hospitalized after protesting or complaining to the authorities.

Many of the people we spoke to were given anti-psychotic drugs, and in some cases electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), without their consent.

There have been reports for decades that hospitalization in China was being used as a way to detain foreign nationals without involving the courts. However, the BBC has found that a problem the legislation was meant to fix has recently returned.

Junjie says hospital staff tied her up and beat her before forcing her to take medication.

His situation began in 2022 after he protested against China’s harsh blockade policy. He says his teachers saw him after just five minutes and contacted his father, who took him to the family home. Her father called the police and the next day – her 18th birthday – two men took her to a Covid testing centre, but they said it was actually a hospital.

“The doctors told me I had a very serious mental illness… Then they tied me to a bed. The nurses and doctors repeatedly told me, because of my views on the party and the government, then I must be mentally ill. It was scary,” he told the BBC. to the World Service. He stayed there for 12 days.

Junjie believes that his father felt compelled to surrender to the authorities because he worked for the local government.

A little over a month after being discharged, Junjie was arrested again. In defiance of the ban on fireworks (a measure to combat air pollution) during Chinese New Year, he made a video of himself setting them off. Someone uploaded it online and the police managed to link it to Junjie.

He was accused of “gathering quarrels and stirring up trouble”, a charge often used to silence criticism of the Chinese government. Junjie says he was forcibly hospitalized again for more than two months.

After being discharged, Junjie was prescribed anti-psychotic medication. We saw the prescription – it was for Aripiprazole, which was used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“Taking the medication made me feel like my brain was a mess,” she says, adding that the police would come to her house to verify that she had taken it.

Fearing a third hospitalization, Junjie decided to leave China. He told his parents he was going back to college to collect his room, but in fact he ran away to New Zealand.

He didn’t say goodbye to his family or friends.

Junjie is one of 59 people the BBC has confirmed – through speaking to them or their relatives, or reviewing court documents – that they have been hospitalized for mental health reasons after protesting or resisting the authorities.

The Chinese government has acknowledged the problem: the country’s 2013 Mental Health Law aimed to stop such abuse makes it illegal to treat someone who is not mentally ill. It also expressly states that psychiatric admission must be voluntary, if the patient is not a danger to himself or others.

In fact, the number of people detained against their will in mental health hospitals has increased, a prominent Chinese lawyer told the BBC World Service. Huang Xuetao, who participated in the drafting of the law, blames the weakening of civil society and the lack of checks and balances.

“I have come across many such cases. The police want power while avoiding responsibility,” he says. “Anyone who knows the shortcomings of this system can abuse it.”

An activist named Jie Lijian told us in 2018 that he was treated for mental illness without his consent.

Lijian says he was arrested for attending a protest demanding better pay at a factory. He says he was interrogated by police for three days before being taken to a psychiatric hospital.

Like Junjie, Lijian says he was prescribed antipsychotic drugs that impaired his critical thinking.

After a week in the hospital, he says he refused any more medication. After fighting with the staff and being told he was causing problems, Lijian was sent for ECT, a therapy that involves passing electrical currents through a patient’s brain.

“The pain was from head to toe. My whole body felt like it wasn’t mine. It was really painful. Electric shock on. Then off. Electric shock on. Then off. I fainted several times. I felt like I was. dying,” she says.

He says he was discharged after 52 days. He now has a part-time job in Los Angeles and is applying for asylum in the US.

In 2019, a year after Lijian said she was hospitalized, the Chinese Medical Association updated its ECT guidelines, stating that it should only be administered with consent and under general anesthesia.

We wanted to know more about the participation of doctors in such cases.

Talking to foreign media such as the BBC without permission could get you in trouble, so our only option was to go undercover.

We booked telephone consultations with doctors working in four hospitals that, according to our evidence, are involved in forced hospitalizations.

We used a fictional story about a relative who was hospitalized for posting anti-government comments online, and asked five doctors if they had encountered cases of patients referred by the police.

Four confirmed.

“The psychiatry department has a type of admission called ‘problems’,” a doctor told us.

Another doctor at the hospital where Junjie was arrested appears to corroborate his story that the police continued to monitor the patients after they were discharged.

“The police will check on you at home to make sure you take the medicine. If you don’t, you may be breaking the law again,” they said.

We approached the aforementioned hospital for comment, but it did not respond.

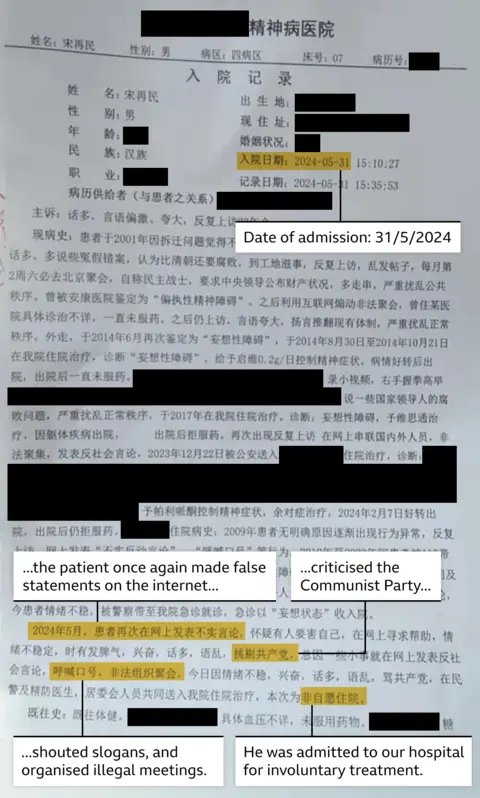

We have been given access to the medical records of democracy activist Song Zaimin, who was hospitalized for the fifth time last year, which makes it clear how closely political views are linked to a psychiatric diagnosis.

“Today, he was talking a lot, talking incoherently and criticizing the Communist Party. Therefore, he was sent to our hospital for hospitalization by the police, doctors and the local residents’ committee. It was a voluntary hospitalization.” he says

We asked Professor Thomas G Schulze, President-elect of the World Psychiatric Association, to review these notes. He replied:

“Because of what is described here, no one should be accepted against their will and treated against their will. It amounts to political abuse.”

Between 2013 and 2017, more than 200 people reported being improperly hospitalized by authorities, according to a group of Chinese citizen journalists who documented abuses of the Mental Health Law.

Their prosecution ended in 2017 when the group’s founder was arrested and later imprisoned.

For victims seeking justice, the legal system appears stacked against them.

A man we are calling Mr. Li, who was hospitalized in 2023 after protesting against the local police, tried to take action against the authorities for his imprisonment.

Unlike Junjie, doctors said Mr. Li was not ill, but police arranged for an outside psychiatrist to evaluate him, who diagnosed him with bipolar disorder, and he was detained for 45 days.

Once released, he decided to challenge the diagnosis.

“If I don’t report it to the police, it’s like I admit to having a mental illness. This will have a big impact on my future and my freedom, because the police can use it as a reason to lock me up at any time,” he says.

In China, the records of anyone diagnosed with a serious mental health disorder could be shared with the police, as well as local residents’ committees.

But Mr Li was unsuccessful – the courts rejected his appeal.

“We hear our leaders talk about the rule of law,” he told us. “We never dreamed that one day we could be locked up in a mental hospital.”

The BBC found 112 people listed on China’s official court website between 2013 and 2024 who tried to take legal action against the police, local governments or hospitals over the treatment.

About 40% of these complainants were involved in complaints about the authorities. Only two won their cases.

And the site appears to be censored: five other cases we investigated are missing from the database.

The point is that the police have “a great deal of discretion” in dealing with those who have “problems”, according to Nicola MacBean of The Rights Practice in London.

“Sending someone to a psychiatric hospital, avoiding procedures, is too easy and too useful a tool for local authorities.”

Chinese social networks

Chinese social networksThey are now looking at the fate of vlogger Li Yixue, who accused a police officer of sexual assault. Yixue is said to have recently been hospitalized for a second time after her social media posts about the experience went viral. It is reported that he is now in custody at a hotel.

We have put the findings of our research to the Chinese embassy in the UK. He said the Chinese Communist Party last year “reaffirmed” that it needs to “improve mechanisms” around the law, which “expressly prohibits illegal arrests and other methods of illegally depriving or restricting citizens’ personal freedom.”

Additional reporting by Georgina Lam and Betty Knight