Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC/Xavier Vanpevenage

BBC/Xavier VanpevenageAnastasiia Fedchenko, 36, cries in anguish; his agony echoes on the gilded walls of St. Michael’s Cathedral in Kiev.

He sits resting his hands on both sides of his stomach. She is heavily pregnant with her first child, a baby girl. Her husband Andriy Kusmenko is a few centimeters away, in uniform – in an open coffin.

The naval commander died in eastern Ukraine on January 4 this year. He is now and forever 33. While Andriy fought in the war, Anastasiia wrote about it as a journalist.

His brothers are passing him in their arms, placing red roses in his coffin. As the funeral prayers end, Anastasia leans forward and gives “the love of her life” one last kiss.

BBC/Xavier Vanpevenage

BBC/Xavier VanpevenageThe outside of the cathedral honors her “most beautiful husband” who died for his country.

“I feel that my daughter will never see her father,” she told the BBC, “but she will know that he was a soldier, an officer, and that he did everything he could so that Ukraine would be there for him and for other generations.”

“This war will last as long as Russia. I am truly afraid that our children will inherit from us and have to go to war.”

Not according to Donald Trump, who says he could end the war in a day and will return to the White House next week. He is already pushing for peace talks between Ukraine and Russia.

This would dishonor the dead, according to Sergeant Dmytro, the “Smile” sign, who fought alongside Andriy and came to cry at the cathedral.

“Let the people in power decide, but I don’t think that those who fell want (the Ukrainian leadership) to sit around the table,” he says.

“After the funeral, we will return to work. We will fight for every fallen Ukrainian.”

Many here believe that – like Anastasia and Dmytro – too many Ukrainians have died to try to make a deal with Russia. But public opinion is changing, and others believe there is too much death and destruction for no deal.

BBC/Xavier Vanpevenage

BBC/Xavier VanpevenageAs Ukraine fights its third winter war, one word is rarely spoken here: “victory”.

In the early days of the Russian invasion in February 2022, we heard it everywhere. It was the cry of a nation suddenly faced with columns of enemy tanks. But the past is really a foreign country, and one with more territory.

Moscow now controls nearly a fifth of its neighbor (including the Crimean peninsula, captured in 2014) and says peace talks must take that into account.

The Ukraine of 2025 is a place of cold, hard realities: cities are emptied, cemeteries fill up, and countless soldiers leave their posts.

BBC/Goktay Koraltan

BBC/Goktay KoraltanA six-hour drive from the capital, in the heart of Ukraine, a young soldier is on the dock.

Serhiy Hnezdilov, a friendly 24-year-old, is locked in a glass cubicle in a packed court in the city of Dnipro. He is being tried on a charge of desertion, and it is one of many.

Since 2022, about 100,000 cases have been opened against soldiers who deserted their units, according to data from the General Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine.

When Hnezdilov left without permission, he publicly demanded a clear deadline for ending his military service. He says he is ready to fight but not without a demobilization plan. It has been going on for five years now, including two before Russia’s full-scale invasion.

“We have to keep fighting,” he told me during a break in the hearing, “we have no other choice.”

“But soldiers are not slaves. Everyone who has spent three years or more on the front line deserves the right to rest. The authorities have long promised to introduce terms of service, but they have not done so.”

He also denounced the corruption and fatal incompetence among the commanders in court.

After a brief procedural hearing, he was handcuffed for the journey back to prison. If convicted, he faces up to 12 years in prison. “Help Ukraine,” he told us, as they led him outside.

BBC/Goktay Koraltan

BBC/Goktay KoraltanMany other Ukrainian soldiers are still straining at the front lines, trying to at least slow down the Russian advance.

Mykhailo, 42, a chain-smoking commander of a drone unit, fights every night fueled by “Non-Stop” – a Ukrainian energy drink.

He is with the 68th “Jaeger” Brigade fighting to hold the eastern front-line city of Pokrovsk, a key transportation hub. The Russians are approaching from both sides.

Mykhailo takes us to a position in Ukraine: a journey we can only risk in the dark, and in an armored car. Even the Russians have eyes in the sky. Their drones are a constant threat. He is alert and tired.

“The first days I went to the enrollment office,” he tells us, “and I hoped that everything would go quickly. The truth is, I’m tired. There are few breaks (in his case a total of 40 days in three years). The only thing that saves me is video chat with my family is that I can.”

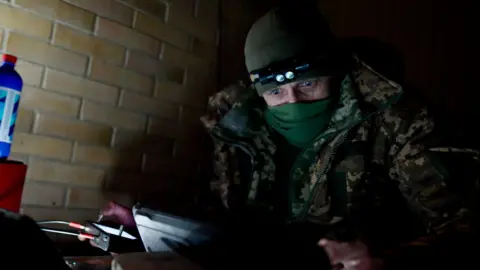

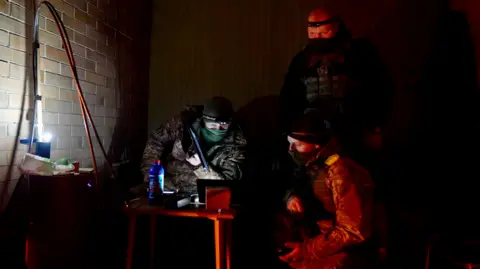

BBC/Goktay Koraltan

BBC/Goktay KoraltanWe arrive at a disused house where Mykhailo and his men unload their gear and set up a pop-up drone position. Screens are included, and cables are connected.

Outside, troops set up an antenna taller than the two-story building. They work quickly under the torch – using red beams rather than white, as these are harder to detect. They then assemble the bombs to arm their “vampire,” an oversized attack drone.

For the next few hours, we have front-row seats as Mykhailo – call sign “Admin” – pilots the drone, eyes darting from screen to screen. First, it drops supplies on front-line Ukrainian troops and then drops anti-tank mortars on Russian forces underground. It’s slightly wide of the target.

It’s against the high wind and Russian jamming. Meanwhile he is looking for enemy drones.

BBC/Goktay Koraltan

BBC/Goktay KoraltanMykhailo spots a Russian warplane in the sky. A few minutes later we hear the distinct crash of three Russian glider bombs. “It’s far,” he tells us. That means two or three kilometers away.

In a lull, I ask Mykhailo if a peace agreement is possible. “Maybe not,” he says. “This (Putin) is a completely unstable person, and that’s putting it very mildly.”

“I hope that at some point the enemy will stop because they are tired, or someone with a good mind will come to power.”

He will not comment on President Trump.

While Mykhailo is a veteran of this war, one of his men is a rookie. Twenty-four-year-old David met last September when the Russians approached his hometown. Now he spends his time handling explosives, although he would rather be studying languages at university.

BBC/Goktay Koraltan

BBC/Goktay Koraltan“No one knows how long the war will last,” he says, “maybe not even the politicians.”

“I would like it to end soon, so that civilians don’t suffer, and people don’t die any more. But the way things are now on the front lines, it won’t be soon.”

He believes that if the guns fall silent it will only be a pause before Moscow returns for more.

The winds get stronger and the vampire drone crash lands. He is currently out. The unit makes up and leaves, just as quickly as it came. They will be back in action at dusk, resuming their duels in the sky.

But on the ground the Russians are still pushing, and a Trump presidency will bring pressure for a deal. And there is one more hard truth here: if it comes, it will hardly be on Ukraine’s terms.

Additional reporting by Wietske Burema, Goktay Koraltan, Anastasiia Levchenko and Volodymyr Lozhko.