Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

PA Media

PA MediaQueen Elizabeth II did not officially announce for almost a decade that one of her most senior courtiers had confessed to being a Soviet spy, according to newly released MI5 files.

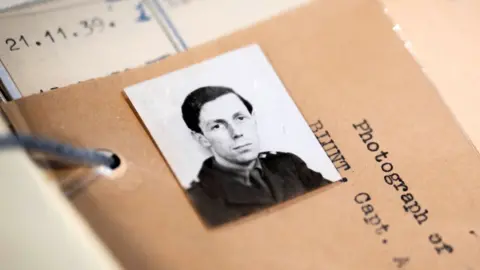

Art historian Anthony Blunt was for decades a surveyor at Queen’s Pictures, which oversees the official Royal Art Collection, and admitted in 1964 that he had been a Soviet agent since the 1930s.

Papers released by MI5 show that although Blunt admitted to spying for the Russians during the Second World War, the Queen herself was not officially informed for nearly nine years.

When he was told the full story in the 1970s, he was incredulous, taking it “very calmly and unsurprisingly,” according to declassified files released to the National Archives.

PA Media

PA MediaThe decision to formally inform the Queen came amid growing concern in Whitehall that the truth would inevitably come out after the death of Blunt, who was terminally ill with cancer. Journalists were already investigating the story and were no longer constrained by libel concerns.

Suspicion first fell on Blunt in 1951, when fellow spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean defected to the Soviet Union.

He had been a close friend of Burgess since they had been together in Cambridge in the 1930s, part of the so-called Cambridge Five spy group.

Blunt worked for MI5 during the Second World War, was interviewed by the Security Service 11 times after 1951, but always denied espionage.

American Michael Straight then told the FBI that Blunt had hired him as a Russian agent.

Getty Images

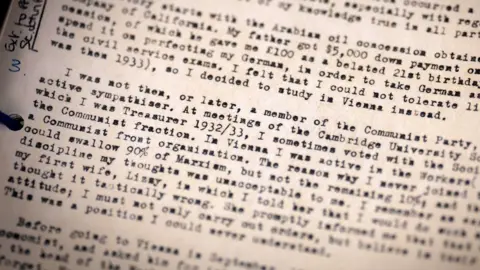

Getty ImagesIn April 1964, MI5 interrogator Arthur Martin confronted Blunt and promised him immunity from prosecution.

His full confession is recorded for the first time in these files. In addition to admitting his work during the war, he also admitted to being in contact with the Russian Intelligence Service after the war.

Blunt said he had met a Russian named Peter before Burgess and Maclean’s departure, but could not remember exactly why. He said that Peter pushed him to run away too, but he refused.

The interviewer said that Blunt was “uncomfortable” as he spoke, and each question “followed a long stride” that “seemed like he was debating with himself how to answer.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite Blunt’s prominent position, few outside MI5 were aware of this confession. They informed the Secretary of the Interior and his most senior official.

The Queen’s private secretary was told only that Blunt had been charged and that he was planning to be questioned by MI5.

It was agreed that if Blunt became seriously ill, he would be officially notified, as this could lead to press coverage of his past.

PA Media

PA MediaAnother file note in March 1973 records that the Queen’s private secretary spoke to Blunt about the case. He says: “He took it all very calmly and unsurprised: he remembered being under suspicion after the Burgess/Maclean case.”

Miranda Carter, Blunt’s biographer, said she had been informally told of her “failure” shortly after 1965.

According to him, officials “wanted to maintain a veil of plausible deniability.” The fact that the monarch took the news “calmly and unsurprised” suggests to Carter that he should have known.

Blunt’s past was finally revealed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in a statement in the Commons in 1979. He died in 1983 at the age of 75, having been knighted.

PA Media

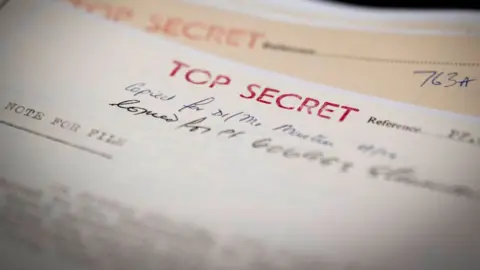

PA MediaUnlike government departments, MI5 is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act. It releases its archives as desired and some files are partially redacted.

Some of the documents released today will appear in an exhibition at the National Archives.

Director General of MI5, Sir Ken McCallum, said: “While much of our work must remain secret, this exhibition reflects our continued commitment to being open where we can.”